Memorial to the suicide bomber

The recourse of suffering by Daniel Villegas

In his trilogy about Cairo, Naguib Mahfuz writes that people who saw themselves doomed to a situation of indigence used to resort to the services of a figure whose trade consisted in inflicting irreversible but not mortal bodily harm, with the purpose of turning these clients into cripples who could practice begging more effectively. In this sense, the phenomenon of exploiting the condition of victim was already classic amongst that community which had no other possibilities for survival.

It is, however, surprising that the extension of this phenomenon of victimisation is manifested in a generalised way in the contemporary world. In our closest context, “owing to a surprising reversal, the fortunate and the powerful, too, wish to belong to the aristocracy of marginality” , that is to say, that of the victims, as Pascal Bruckner puts it. Thus, as Bruckner sees it, the state of generalised victimisation is a response to the conditions of a social context in which suffering and its victims have been made sacred as a result of a process of infantilisation of the world and of subjective irresponsibility with respect to the vicissitudes of life. This mechanism, of a psychopathological nature in its more obsessive versions, “(…) allows to exercise a persistent desire for power over those closest to one (…) The most minimal adversity is then enlarged until reaching the dimensions of a major event; it turns into a stronghold from which to give lessons to others, while remaining free of criticism (…), claiming to be persecuted turns into a subtle way of persecuting others”.

The prestige enjoyed by victims, real or simulated, in contemporary societies is such that it has turned into an enviable condition for a group of simulators for whom “being a victim will turn into a vocation, into a full-time job”.

In this situation, as Bruckner points out, a climate based in a relationship of mutual distrust is created, in which there is always the certainty that someone is conspiring against us. This atmosphere of generalised suspicion produces a retreat, an entrenchment, which does not permit to define even the most minimal collective project. The phenomenon of suspicion towards everything and everyone has been defined by Peter Sloterdijk as atmoterrorism ; once the different scores with the legitimating instances of the modern knowledge-power have been settled by those who have arisen as its victims, we will have to live in a strained atmosphere.

In any case, a problem may be inferred from the generalised situation of victimisation, more worrying, if possible, than the one already pointed out – that of the appropriation and/or supplanting of the voice of the real victims by the simulated victims. Thus, we are already accustomed to the manipulation of another’s suffering by those who pretend, or simulate, to be the object of the same condition. It is usual that the one who is able to present oneself as the spokesperson for the calamities of certain individuals or groups, despite not having been exposed to the conditions that make them into victims, occupied the front line of the process of victimisation. This is a form of exploitation that permits to obtain large benefits. We can find numerous examples of exploiting victimization in the cultural sphere in general, and contemporary art in particular, and very especially in those artists and events that employ political and social issues as their work material. In this sense, George Yúdice analyses the exploitation of the cultural manifestations of groups of victims of inequality or social situations. Yúdice treats in this context the border project inSITE, and within it, and of great interest with respect to the irresponsible exploitation of victims, particularly the work of Krzysztof Wodiczko about the Tijuana maquiladora factories.

Be it as a simulacrum or as the exploitation of the condition of victim and victimisation processes, the extraordinary importance of these phenomena in the articulation of our contemporary societies seems to be doubtless. As Yúdice maintains in reference to culture, suffering has become one of the main recourses of our desire for power.

All of you are guilty except me

by John Peter Nilsson

In the remarkable movie “Paradise now” (2005), co-written and directed by the Dutch-Palestinian Hany Abu-Assad, wefollow two Palestinians everyday life in the closed Gazastrip. To begin with they seem to be totally unpolitical and notespecially religious. But in the next 36 hours, the two childhood friends may do the unthinkable. Without any hopes forthe future and feeling entrapped by the Israeli military, they are being recruited to commit a suicide bombing in Tel Aviv.What is interesting in the film is its “everydayness”. The friends decision to die doesn’t come from an ecstatic belief tochange the political life in the Middle East. Neither from a wish to become a mature. The decision is rather pragmaticand comes from boredom. Nothing will change in the area, they are for ever doomed to live their poor lives, humiliatedby the Israeli rulers. So of two bad choices they choose the least bad: Maybe there is a paradise after all – and why nottry for it now.It is an extremely pessimistic film. It explains terrorism in a partly, at least for me, new way – terror as a private escapefrom hell. I condemn terror in all forms, especially when innocent civilians die. But it is a rather complex discussion -one can assert that killing a few can save many. But this is another discussion…

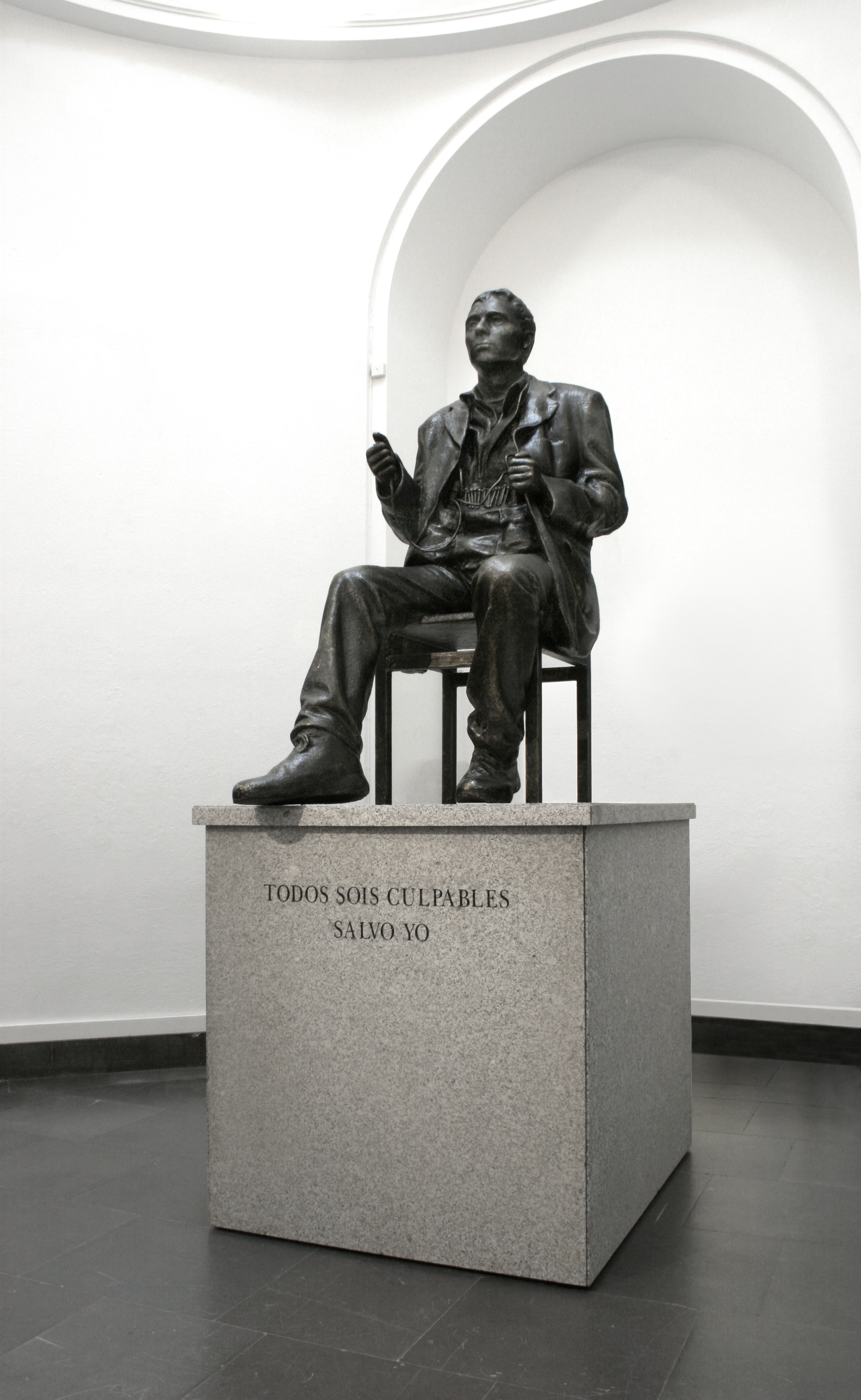

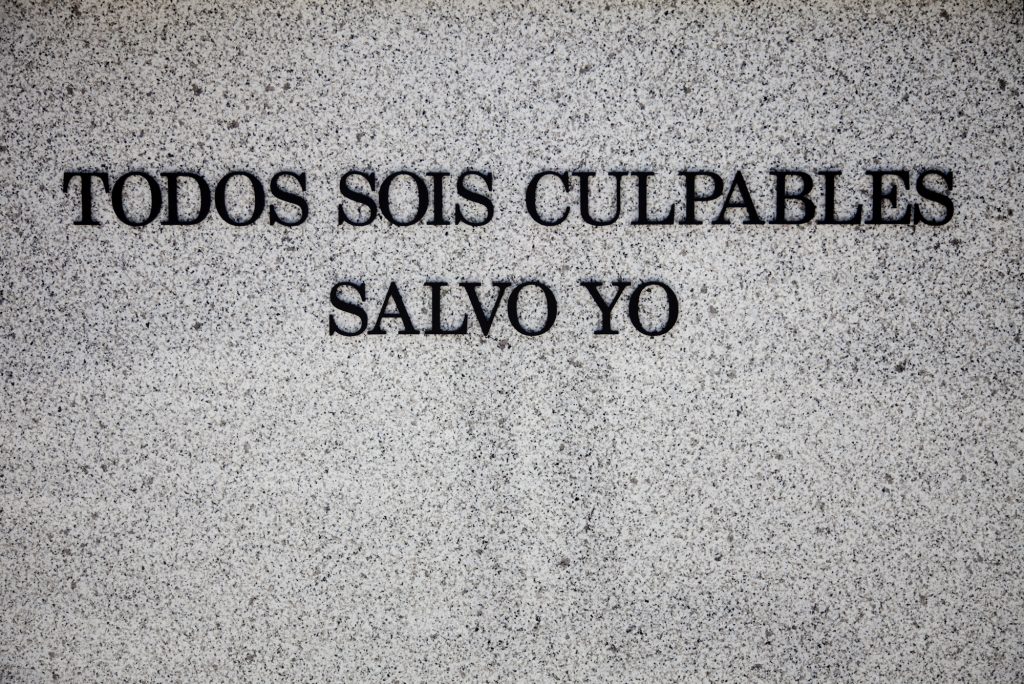

The new sculpture by Democracia has monumental proportions: 3,30 metres high. But it also is a monument. A man issitting on a chair that stands on a pedestal in granite. There is also an inscription: “All of you are guilty except me.” It couldbe a famous writer sitting there. Or a political leader, a philosopher? But when one look closer from the front the manopens up his jacket a bit. Around his belly there are bombs. He is a suicide bomber.

As usual when confronted with Democracia’s work (earlier also El Perro’s) one feel provoked. Is this a celebration ofterrorism directed against civilians? But of course it much more intricate. On one hand the sculpture discusses the concept of memorials. What is behind the immortalization of the many men (unfortunately it is sadly often men) that deserve to be remembered for ever? History changes. We know the polarization in the former Soviet Union after the fall ofthe wall between those that wanted to keep the Lenin’s and the Stalin’s or not. How many dead bodies, literally andsymbolically speaking, are hidden before a monument is built? Democracia’s sculpture is deconstructing the phenomena of historical monuments.

But on the other hand the sculpture is also dealing directly with generalized victimization in the today’s society. “All you are guilty, except me” is what the suicide bomber is remembered for. The inscription, and also that the suicide bomberis sitting on an elevated pedestal, give the work a surprising perspective. It’s not the perspective of the victimized butrather of the perpetrator. I am reminded of the19th century writer Thomas de Quincey who said that an artwork about a murder is not a story about murder but murder itself. When looking at a murder scene, the perspective cannot be thatof the victim but of the murderer – or the viewer. If one really succeeded in assuming the victim’s point of view, the fearwould be so overwhelming that an aesthetic experience would not be possible.

Yes, we are guilty by looking away of fear. By only suicide bombings as pure violence and not taking the political or religious messages for real in order to start dialogues, we might create a society in which we feel like prisoners, not unli-ke the society in the above mentioned “Paradise now”. Boredom and pessimism may occur, and terrorism become thenext jackass challenge?